Local History: Untold Stories

Giving a voice to those who had none...

In the 1700s, the West Springfield High School property was a part of a large plantation owned by the Fitzhugh family called Ravensworth. In the 1820s and 30s, Presley Barker, who owned a small farm in our area, purchased a portion of the Ravensworth estate, including the future site of our school. Both the Fitzhugh and the Barker families were slaveholders, and West Springfield’s Applied History students have been working to document the lives of the enslaved individuals who lived on or near our school property. The goal of this work is to preserve their memory and share their story, a story heretofore untold.

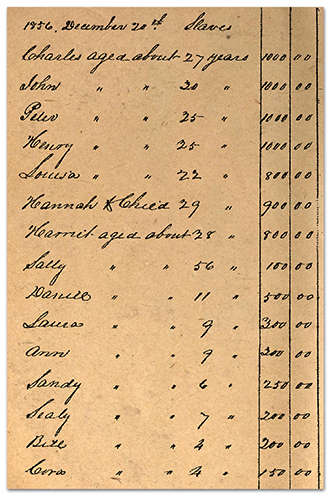

After Presley Barker passed away in 1856, the Fairfax County Circuit Court ordered an appraisal of his real and personal property. The preceding list is a portion of Barker’s estate inventory. It lists the names, ages, and value in dollars of the enslaved individuals held by Barker. The purpose of the inventory was to define an accurate value for each person so that these individuals, as property, could be divided equally among the heirs of Presley Barker.

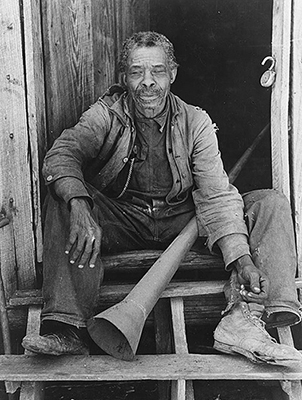

Daily Life of Slaves

The quality of life of a slave varied whether one was enslaved on a large tobacco plantation, a small family farm, or a fast-paced urban environment. Slaves in Fairfax County, including the Barker slaves, could have been exposed to all three ways of life.

Life on a Small Farm

- For slaves working on small farms, the work was a little less tedious than tobacco cultivation, but no less demanding. In addition to caring for livestock and general farming, slaves could be expected to do household tasks such as cooking and cleaning.

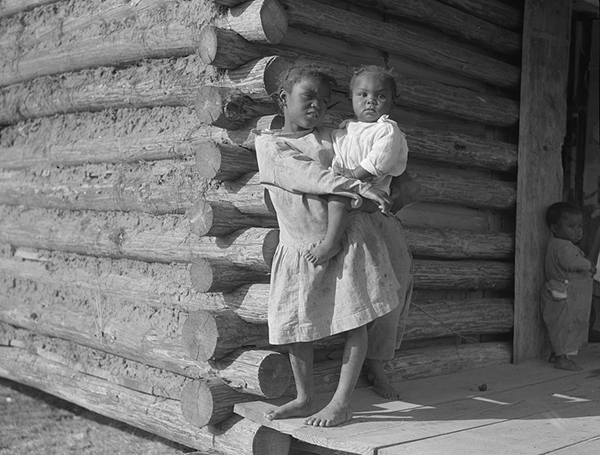

- Slaves on small farms often slept in the kitchen or an outbuilding, and sometimes in small cabins near the farmer’s house.

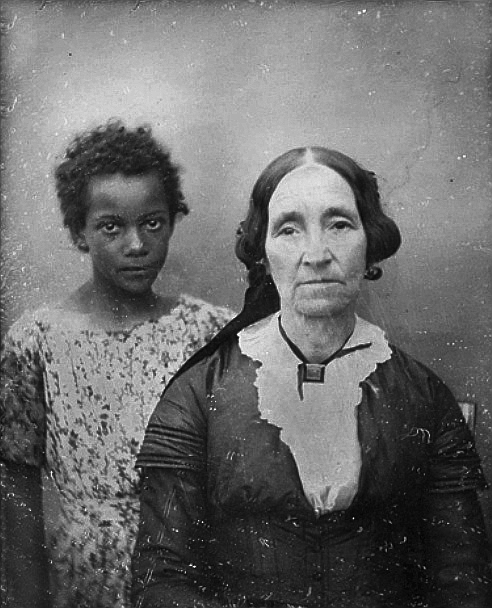

- Because the small farmer owned only a few slaves, it was hard for slaves on these farms to find wives and husbands. Some had family on nearby farms, and, on occasion, their masters allowed them to visit with one another.

Life on a Plantation

- Generally, slaves on plantations lived in complete family units, their work dictated by the rising and setting of the sun, and they generally had Sundays off.

- Plantation slaves were more likely to be sold or transferred than those in a domestic setting.

- On larger plantations where there were many slaves, they usually lived in small cabins in a slave quarter, far from the master’s house but under the watchful eye of an overseer.

Life in Towns and Cities

- Slaves in urban environments had more mobility because they weren’t tied to an agricultural calendar, so they had a different rhythm of work. Job tasks ranged from butlers and carriage drivers, to cooks, dock workers, and more. Also, skilled male slaves often worked alongside whites.

- Slaves usually lived separate from their owners; there were even communities on the outskirts of cities where free and enslaved people of color lived side-by-side.

- Some cities and even churches owned slaves; these slaves would do all kinds of infrastructure work such as making sure the roads were smooth or making repairs to buildings.

- An example of this is Savannah, Georgia where the companies in the timber and brick industries held a large number of slaves.

Things in Common

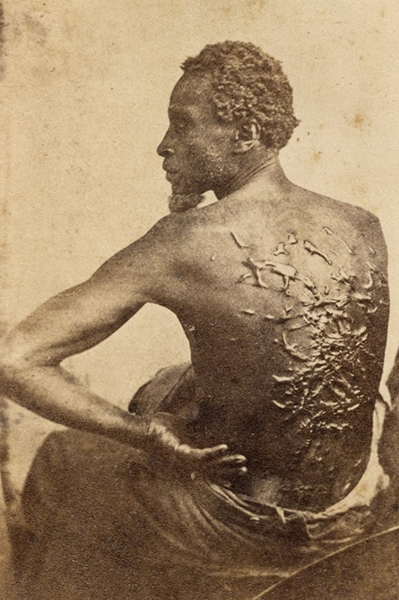

Slaves on small farms and plantations were busy year-round caring for crops and livestock, often working from sunrise to sunset. Slaves on plantations and in urban settings were more likely to be skilled in a specific trade. However, no matter what setting in which they worked, slaves could be subjected to brutal and severe punishments.

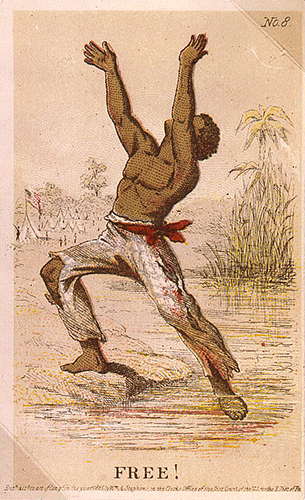

Slaves could be rented out by their masters and passes were required to travel everywhere. Slaves travelling the Underground Railroad to freedom often used forged documents when travelling, and were guided by spirituals, songs with specific meanings hidden in the lyrics that might direct a slave where to travel, how to avoid detection, and whether or not a place was safe to approach.

In was common for enslaved families to be split apart because the individuals, as property, could be bought, sold, or bequeathed to an heir. In northern slave-holding states, chronically disobedient slaves were sold to cotton and sugar cane plantations in far-away states like Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.

By Comparison

Enslaved individuals were often highly skilled laborers and many of the jobs they did 150 years ago correspond with modern careers or branches of study we learn in high school.

- Blacksmith: chemistry, geometry

- Carpenters: arithmetic, algebra, geometry, calculus and statistics

- Tanner: chemistry

- Coopers and Smiths: woodworkers and metalworkers

- Cordwainer: shoe designers and manufacturers

- Weaver, Spinner, and Quilter: artists, clothing designers and manufacturers

As we examine the inventory of the property owned by Presley Barker in closer detail, we can begin to make some educated guesses about what life may have been like for the Barker slaves. The first thing one notices is that each person is assigned a monetary value. The values correspond with age and gender. The men between the ages of 20 and 27 had the most value because they were young and able bodied. Sally, at age 56, was possibly in ill-health and may have no longer been able to bear children so her monetary value was the lowest of all. Any children born to the female slaves, including Hannah's unnamed child, would have become property of the Barker family.

Slave Inventory

- Charles, age 27, value $1000

- John, age 20, value $1000

- Peter, age 25, value $1000

- Henry, age 25, value $1000

- Hannah & Child, age 29, value $900

- Louisa, age 22, value $800

- Harriet, age 38, value $800

- Daniel, age 11, value $500

- Ann, age 9, value $300

- Laura, age 9, value $300

- Sandy, age 6, value $250

- Sealy (Celia), age 7, value $200

- Bill, age 4, value $200

- Cora, age 4, value $150

- Sally, age 56, value $100

Presley Barker’s estate inventory also recorded that he owned a house in Alexandria on Queen Street and several types of livestock, farming implements, and household items. From this, we can infer that the Barker slaves raised cows, sheep, pigs, chickens, geese, and horses. They also planted and harvested potatoes, turnips, cabbage, wheat, oats, corn, and beans. The presence of a hogshead in the inventory (a very large barrel used to haul tobacco to market), was probably a holdover from an earlier time when tobacco was the principal farm crop. There are indications that one or more of the men worked as blacksmiths and wagon drivers. The presence of a milk house and meat house shows evidence of dairy and meat preparation for home use and perhaps for sale as well. Some of the women likely worked as house slaves at the home in Alexandria.

The Division

Presley Barker’s heirs at the time of death were his widow, Charlotte, and their two children, Ulam and Willie. The slaves and land owned by Barker was divided between each of the heirs. Henry, Peter, Harriet, and Laura became the property of Charlotte Barker. John, Hannah and her unnamed child, Ann, Cora, and Sandy became the property of Willie Barker. Ulam Barker inherited Charles, Daniel, Celia (Sealy), Bill, and Louisa. It is unknown at this time whether or not they were divided by family groups.

Created by Seana Ellsworth, WSHS Applied History, Class of 2018